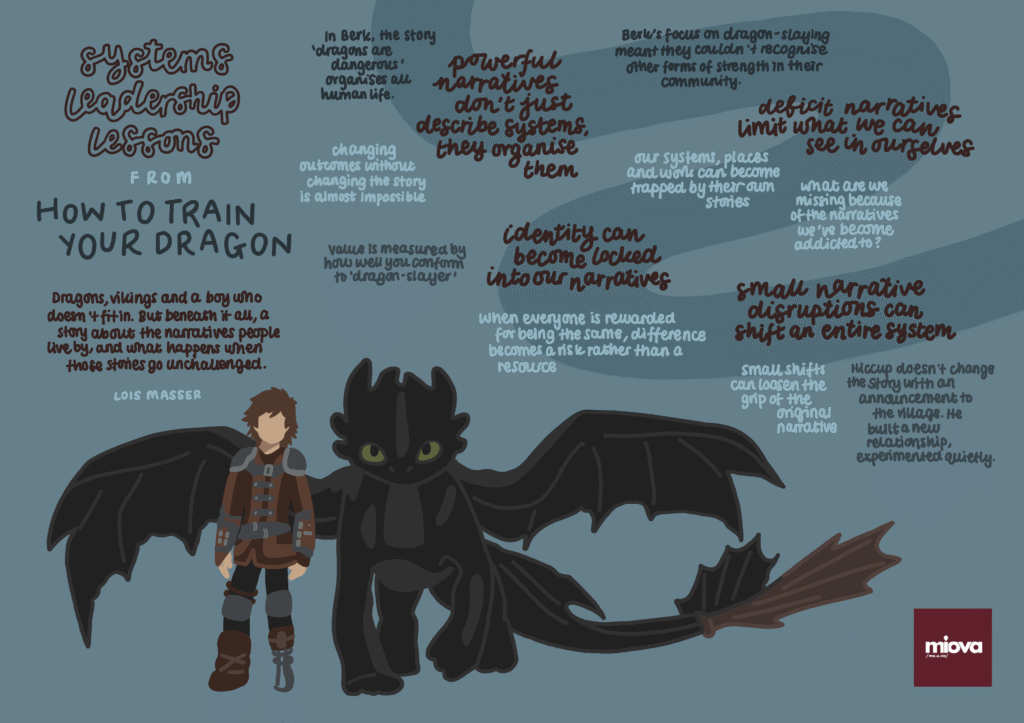

Not all films stay with us. But some quietly shape how we think long after the credits roll. How to Train Your Dragon is one of those films for us at Miova. Maybe not a conventional topic for a systems thinking blog… but beyond the dragons, Vikings and a boy who doesn’t fit in, this children’s film tells a story about the narratives people live by, and what happens when those stories go unchallenged.

Set in the Viking village of Berk, the film follows a community shaped by a single belief: dragons are dangerous and must be destroyed. When Hiccup, a young boy who doesn’t fit the mould of a dragon-slayer, forms an unexpected friendship with a dragon, that belief, and the system built around it, begins to unravel.

Lesson 1: Narratives don’t just describe systems, they organise them

In Berk, the story that “dragons are enemies” doesn’t sit at the edge of village life, explaining some of the Viking’s behaviour. It organises everything: how children are trained, which skills are valued, and who is afforded status or leadership legitimacy.

The same is true in our work with places and systems. Once a powerful narrative takes hold, behaviours, structures and processes begin to align around it. The story becomes the system’s operating logic. As systems thinker Donella Meadows asked, “How is it that one way of seeing the world becomes so widely shared that institutions, technologies, production systems, buildings, cities, become shaped around that way of seeing?”

Changing outcomes without changing the story is almost impossible. If Berk banned dragon-slaying while continuing to reinforce how dangerous dragons were, would the Vikings really have stopped hunting them? Rather than changing policies or incentives alone, it was the shift in narrative that proved transformative , reshaping culture and the way people lived, related and belonged.

Lesson 2: Deficit narratives limit what a place can see in itself

Berk’s story was rooted in fear. That narrow focus blinded the village to its own adaptability, ingenuity and range of strengths. Physical strength and dragon-slaying were prized so highly that other qualities (curiosity, empathy, careful observation and quiet determination) were ignored. Hiccup’s strengths were there all along; the story simply made no room for them.

This raises an uncomfortable question for our own work. What strengths in our places or teams are we missing because of the narratives we’ve become addicted to? Perhaps there is someone in your organisation who excels at organising, connecting or creating coherence. But if the dominant story says that only visible or external-facing work matters, those strengths are overlooked, and the system continues to struggle with problems it already has the capability to address.

Berk had the potential to be a place of innovation, interdependence and balance with its environment. It didn’t need new resources to become that place. It needed a new story about itself.

Lesson 3: Identity can become locked into narratives

When a narrative takes hold of a system, it doesn’t just shape what is valued; it shapes who people believe themselves to be. In Berk, worth was measured by how well you conformed to the role of dragon-slayer. If you didn’t fit, you weren’t just unsuccessful, you were less than.

We see the same dynamic in many workplaces and public systems. In organisations where being “good” is defined by visible delivery, pace or constant busyness, people whose strengths lie in reflection, relationship-building or systems thinking can find themselves marginalised, even when those capabilities are exactly what the system needs.

This kind of identity lock-in creates fragile systems. When everyone is rewarded for being the same, difference becomes a risk rather than a resource. What looks like strength on the surface is often rigidity underneath. Releasing identity from a single story of value isn’t about lowering standards or removing accountability, it’s about widening the narrative so more people can belong and contribute meaningfully.

Lesson 4: Small narrative disruptions can shift entire systems

Narratives rarely change through grand announcements. They shift because people behave differently. In the film, Hiccup doesn’t start by persuading the village. He builds a different relationship, experiments quietly and tells a new story through action rather than argument.

Those small disruptions spread through trusted relationships and eventually across the village. By the end of the film, Berk has changed in visible ways. Dragons are no longer hunted but integrated into daily life. What counts as strength and leadership has shifted, and the village reorganises itself around cooperation rather than conflict. The place is the same, but the story it lives by is not.

In terms of a real life example, we see similar dynamics in systems shaped by the narrative that good organisations eliminate risk. Although often rooted in care and accountability, this narrative can slow decision-making and suppress experimentation and learning. Change begins with small disruptions: reframing conversations towards learning, naming uncertainty, treating pilots as experiments rather than commitments. Over time, these actions tell a different story – one where curiosity and shared responsibility can take root.

As Margaret Wheatley reminds us, “There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.”

Closing reflection

How to Train Your Dragon reminds us that the most powerful force in any system is often the story it lives by. And that change often begins with noticing the stories we’ve stopped questioning.

In Berk, the narrative wasn’t malicious; it was protective, logical and deeply held. And yet it still limited what the village could see, value and become. The same is true in our places and organisations. Even well-intentioned stories can narrow identity, hide strengths and lock systems into patterns that no longer serve them. If we want different outcomes, the work may not be to replace one story with another, but to notice when a narrative has begun to organise too much, and to create space for new meanings, relationships and possibilities to emerge.

Perhaps the hardest work isn’t training the dragon, but noticing how we’ve been trained by the dragon story.